2

foundations

PALESTINE EMERGING seeks to complement ongoing national efforts with informed long-term strategies. We focus on Palestine’s potential as a globally-connected, competitive economy.

SOCIO-ECONOMIC CONTEXT

PALESTINE EMERGING anticipates ways the Palestinian economy can benefit from local and macro-trends already shaping other urban territories worldwide, build on its rich heritage, and overcome decades of constraint. For this purpose, we make assumptions about future conditions in Gaza, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem with a regional perspective; specifically, these relate to:

- Overall political conditions (regional openness; removal of current constraints; Palestinian statehood)

- Economic relationships (state/city-level economic cooperation within region)

- Infrastructure (connectivity across Gaza and region)

TIMESCALES

For our purposes, we consider three timescales to provide a context when considering challenges and opportunities for Gaza and the West Bank:

- Short term (by 2030)

- Medium Term (by 2040)

- Long Term (by 2050)

UNDERSTANDING PALESTINE (context and baseline)

Achieving the PALESTINE EMERGING growth scenario will require decades of concerted efforts, large-scale investment and relaxation of the multi-layered system of restrictions that have hindered growth and employment in the Palestinian economy. The onset of war in 2023 exacerbated a long-standing history of economic dependence, fragility, volatility and poor overall performance.

PALESTINE EMERGING ANTICIPATES A GROWTH ALTERNATIVE TO A CONSTRAINED STATUS QUO

STATUS QUO Scenario

(constrained conditions)

- Sustained political and economic constraints

- Local zero-sum advantages with Israel

- Natural population growth until 2030

- Constraints to movement/trade partially lifted

- Lingering reliance on Israel

- Subordinate control of Gaza and West Bank

PALESTINE EMERGING Scenario

(growth conditions)

- Decreasing political and economic constraints

- Equitable engagement with broader region

- Substantial population growth

- Constraints to movement/trade fully lifted

- Diminishing reliance on Israel

- Sovereign control of Gaza and West Bank

1

A volatile and “partitioned” economy, underperforming against the region

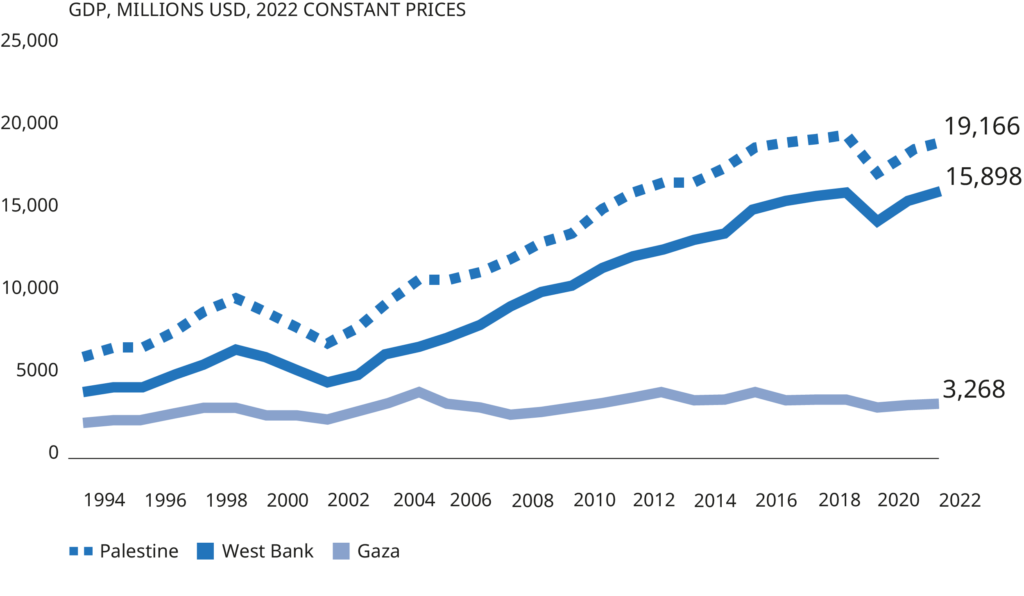

Figures 1-2 below show growth patterns that characterize Palestine´s fragmented and volatile economic structure. Conflict-linked shocks dominated the last 20-30 years (with major negative impacts in the late 90s and early 2000s). The relative performance of Gaza and the West Bank remained closely correlated until the mid- 2000s, as the Gaza Strip experienced an economically crushing blockade after Hamas came to power.

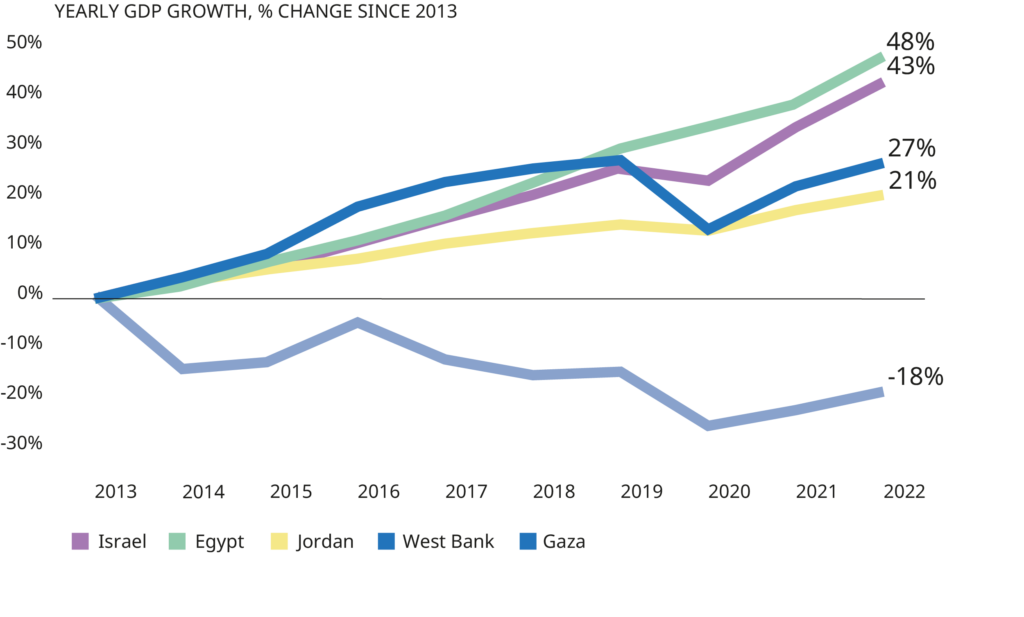

From 2006, GDP grew most years in the West Bank, but stagnation and volatility dominated Gaza. Figure 3 demonstrates this divergence, with the West Bank showing resilience even during the six periods of strong negative growth following conflict-driven shocks in Gaza.

While GDP per capita almost doubled in the West Bank from 1994-2022 (despite a strong drawback during the pandemic, which also affected Gaza greatly), Gazans are poorer today than in 1994. Figure 2 shows how the negligible difference in GDP per capita observed between regions in that year widened from 2006, with West Bank GDP per capita more than 260% higher than that of Gaza in 2022.

The relative decline of Gaza has depressed the economic performance of the Palestinian economy against the wider region over the last decade (Figure 3). As a result, while GDP per capita in the West Bank is higher than in Egypt and Jordan (Figure 4), the West Bank and Gaza combined underperform those comparative economies (with Gaza´s GDP per capita close to levels observed in poor Sub-Saharan African countries and 36 times lower than in neighboring Israel – itself a major driver of instability).

GDP GROWTH IN PALESTINE HAS BEEN DRIVEN BY THE WEST BANK

Figure 1 | PCBS (2022)

GDP PER CAPITA HAS BEEN CONTRACTING IN GAZA

Figure 2 | PCBS (2022)

GDP HAS INCREASED BY 27% IN WEST BANK SINCE 2013, CONTRACTED BY 18% IN GAZA

Figure 3 | PCBS (2022)

GDP PER CAPITA IN PALESTINE TRAILS OTHER REGIONAL ECONOMIES

Figure 4 | PCBS (2022), WORLD BANK WORLD DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS

2

A low productivity economy dominated by non-tradable sectors

In any given economy, “leading” or “specialized” tradable sectors (e.g. manufacturing, tourism, export-oriented digital services) drive activity, growth and employment, accompanied by “supporting” industries (e.g. public services, health and education, retail and commerce).

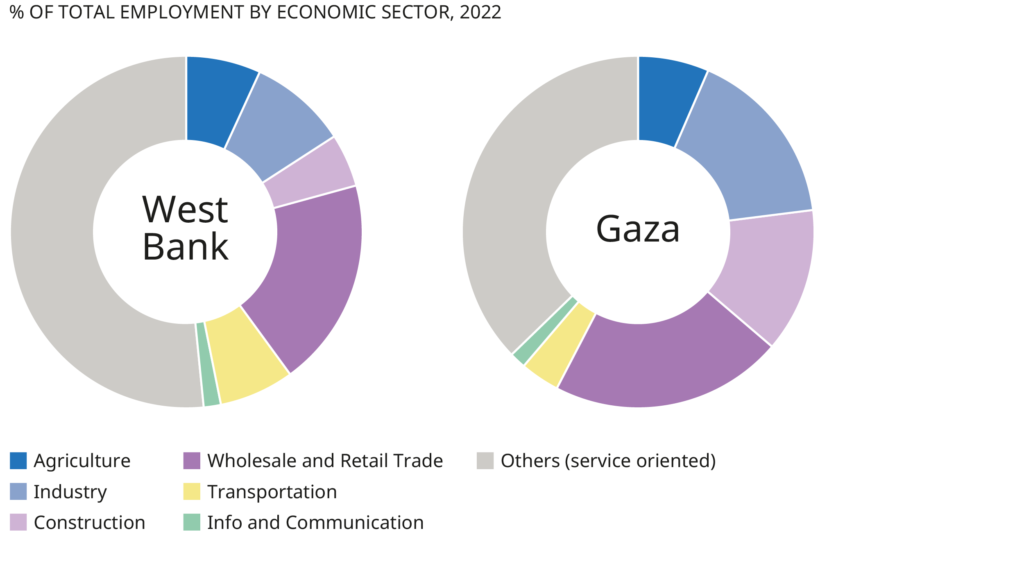

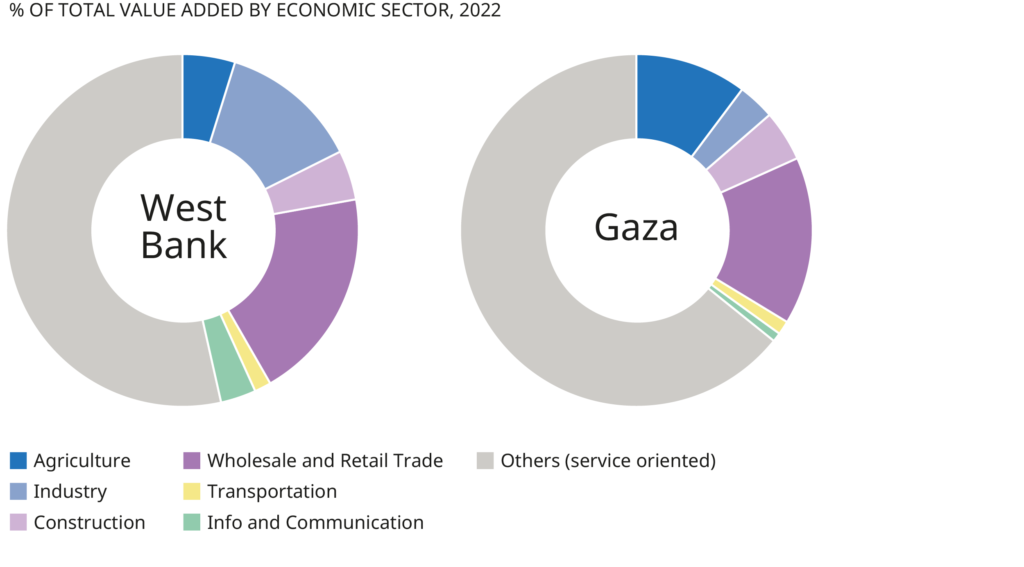

In Palestine, the weight of high-value, high-productivity, export-oriented industries in total employment is relatively low (Figure 5), where low-value services and wholesale retail employment make up the majority of all employment.

Most value added sectors are service oriented (Figure 6), with tradables and dynamic industries seriously hindered by Israeli-imposed restrictions on the movement of people and goods in the whole of Palestine

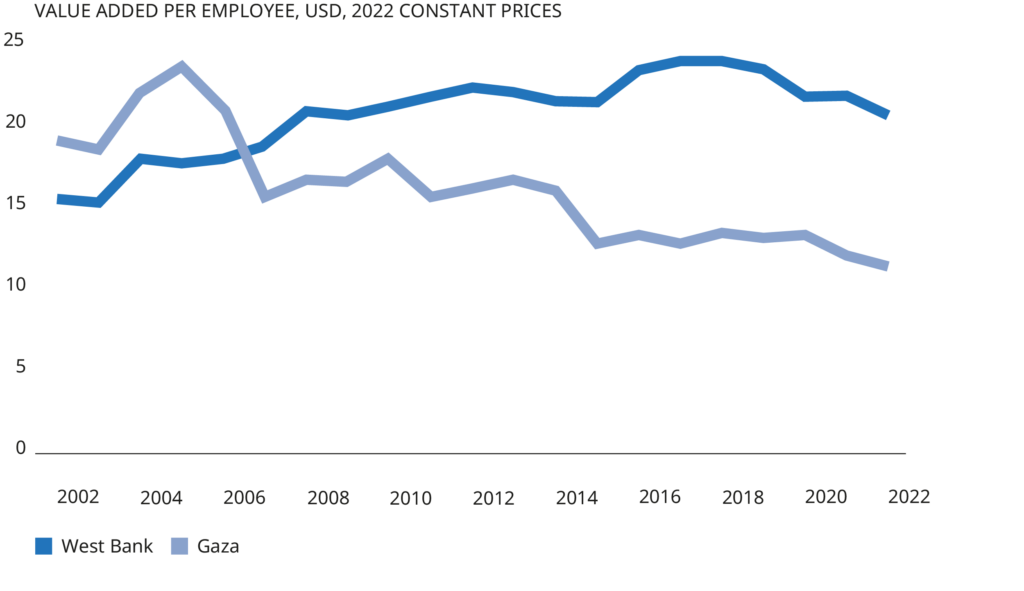

As a result, labor productivity, measured by value added per employee, has remained largely stagnant in the West Bank over the last two decades, and in Gaza dropped to its lowest levels in 2022 (Figure 7), even before the latest round of violence. To achieve the aspiration of sustainable growth, it is essential to transition to higher value, export oriented, higher productivity sectors, making the most of the enormous untapped potential for economic diversification across Palestine.

EMPLOYMENT IS CONCENTRATED IN FRAGMENTED SERVICE-ORIENTED SECTORS AND WHOLESALE RETAIL…

Figure 5 | PCBS (2022)

…WHICH ACCOUNT FOR AN EVEN LARGER SHARE OF TOTAL VALUE ADDED

Figure 6| PCBS (2022)

LABOUR PRODUCTIVITY HAS BEEN TRENDING DOWN FOR BOTH West Bank AND GAZA

Figure 7 | PCBS (2022)

3

Unemployment (and underemployment) are stubbornly and dangerously high, especially among youth

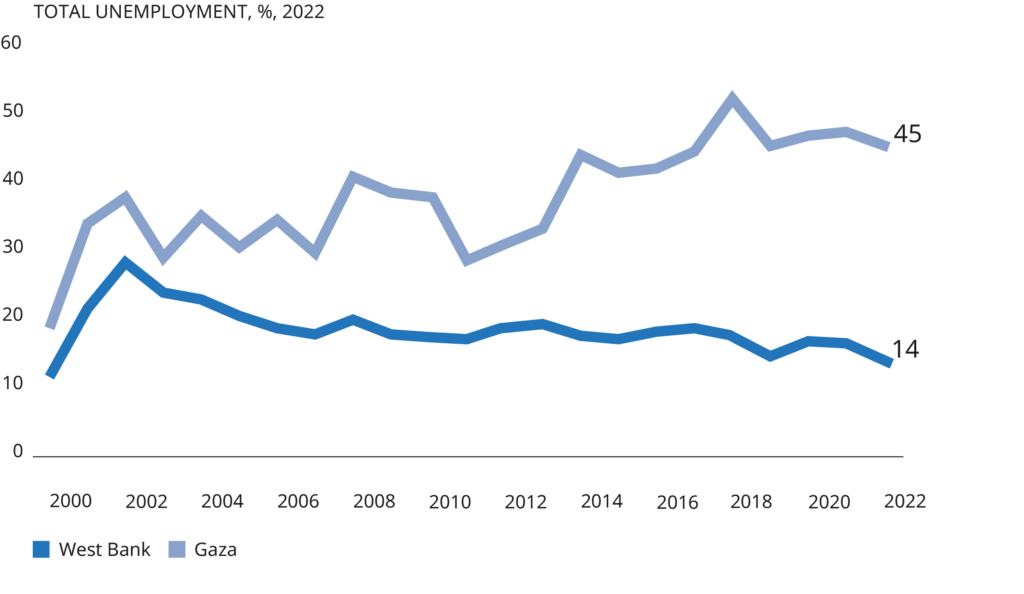

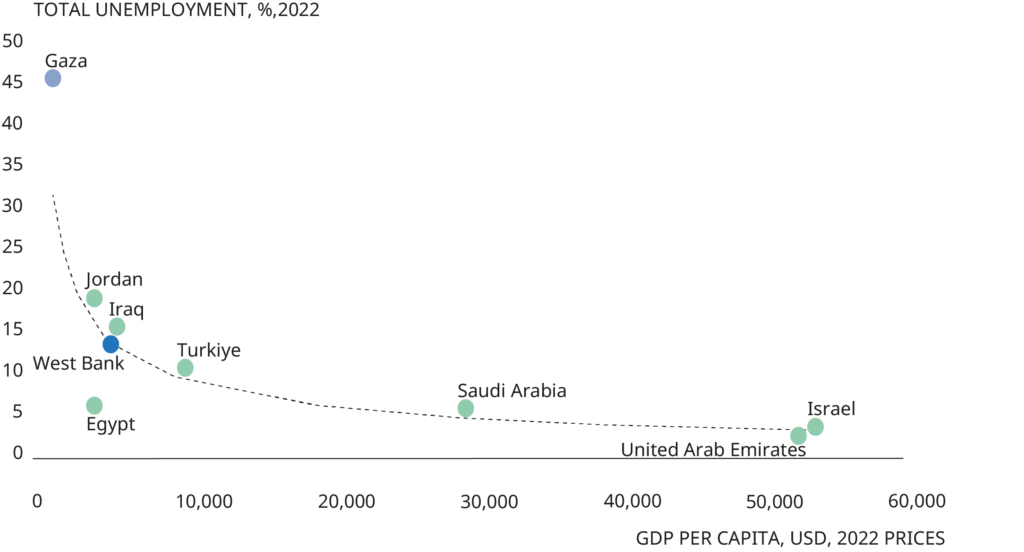

Poor growth and other characteristics discussed above correlate strongly with high unemployment (Figure 8). This is certainly true in the case of Palestine, with Gaza presenting alarmingly high rates of joblessness, both in absolute terms and in comparison to the wider region. In the West Bank, total unemployment has been resistant to economic growth, especially from 2006-2007, when it remained consistently above 10% despite periods of stronger economic performance.

At the same time, consistent with the start of “divergent” trajectories between the Palestinian regions, overall unemployment in Gaza spiked to staggeringly high levels, reaching 45% in 2022, before the 2023 war (Figure 9), the highest in the region.

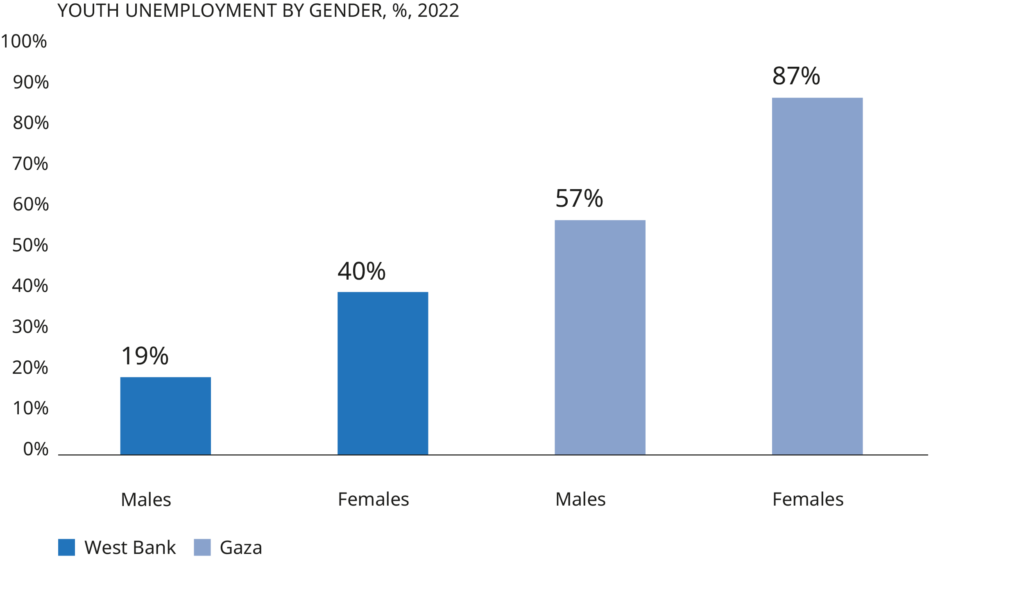

The situation is particularly dramatic among women and young people, with nearly 9 in 10 female labor market participants aged 15-24 unemployed in Gaza in 2022 (Figure 10). Rebuilding the employment base with stable, high-quality jobs following economic diversification is crucial for prosperity and stability in the region.

WITH CLOSE TO HALF THE POPULATION UNEMPLOYED…

Figure 8 | PCBS (2020, 2023a)

…GAZA HAS AMONG THE WORST RATES OF UNEMPLOYMENT AND GDP PER CAPITA IN THE REGION

Figure 9 | PCBS (2023a), WORLD BANK WORLD DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS

YOUTH UNEMPLOYMENT RATES ARE HIGHER FOR WOMEN IN BOTH WEST BANK AND GAZA

Figure 10 | PCBS (2023b)

4

Palestine´s relationSHIP with the Israeli economy is one of imbalance AND CAPTIVITY

It is impossible to understand Palestine’s economic structure without acknowledging the norms and restrictions defined by Israel that affect all economic activity, including trade and exchange. Norms include Palestine’s dependency on the Shekel, with a consequent lack of optimal monetary orientation.

The current customs union and the high dependency on taxes collected by Israel on behalf of the Palestinian Authority (PA) also results in fiscal fragility. Restrictions, originally imposed on security grounds, include Israel’s long-standing control over activities in the West Bank. These constraints include barriers to movement of people and goods from the West Bank and Gaza, restrictions on aquifer access, and limits on mobile communications standards. They also impose low-quota restrictions on banking activities (e.g. cash shekel transfers to Israeli banks).

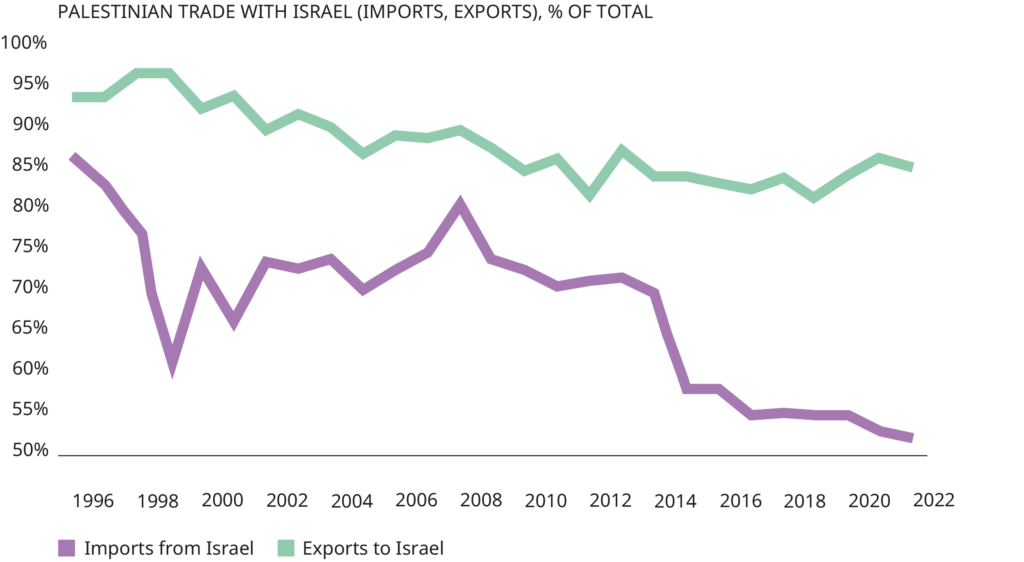

In this context, preconditions for sustainable growth include greater openness, economic diversification, and mutually advantageous links with Israel (recognizing proximity to a high-income OECD economy is a competitive advantage, yet to be fully exploited). Palestine’s import and export trade with Israel remains high despite decreasing intensity in the past few years (Figure 11).

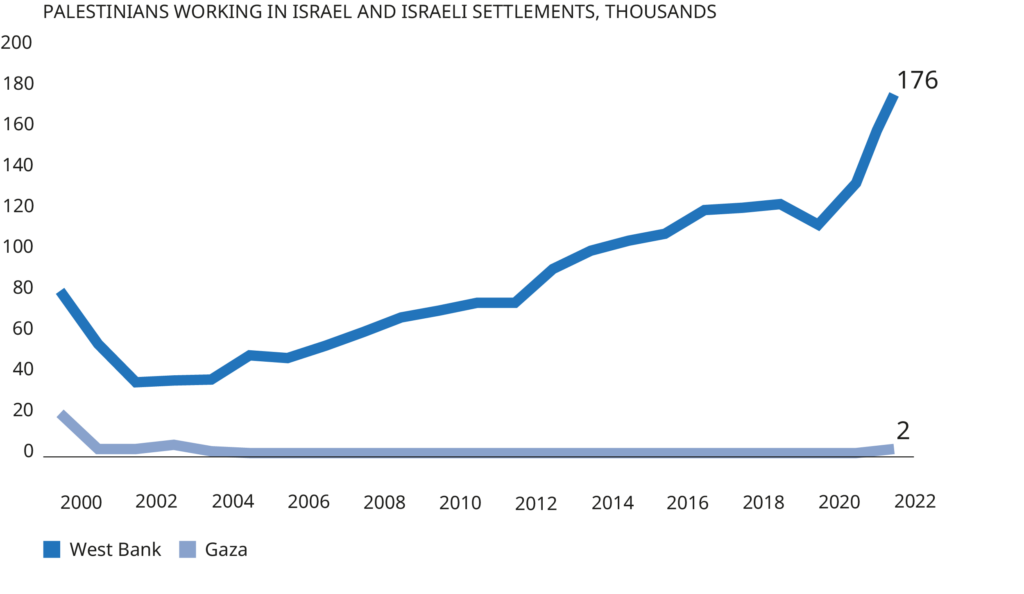

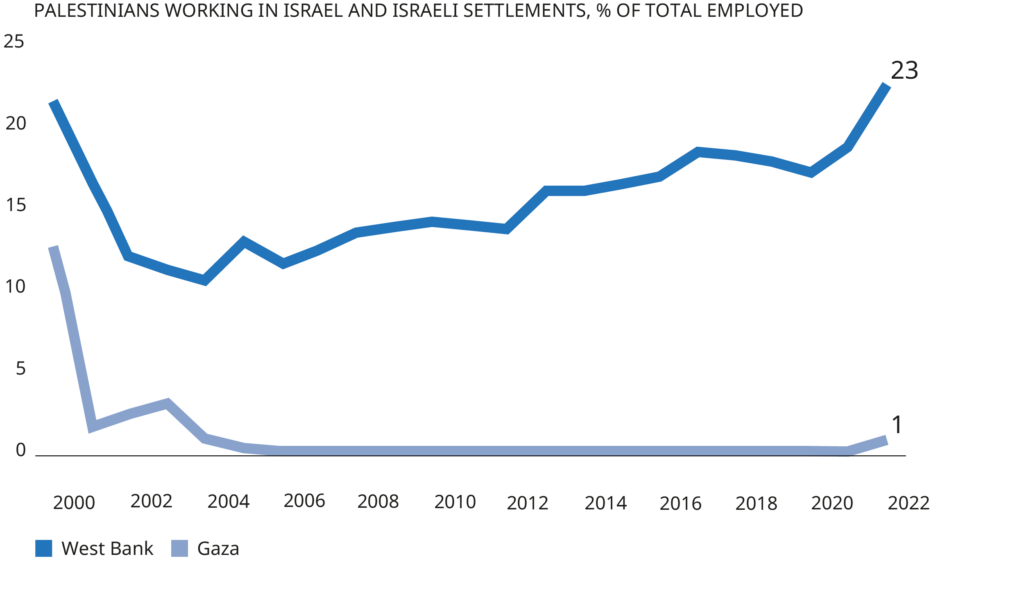

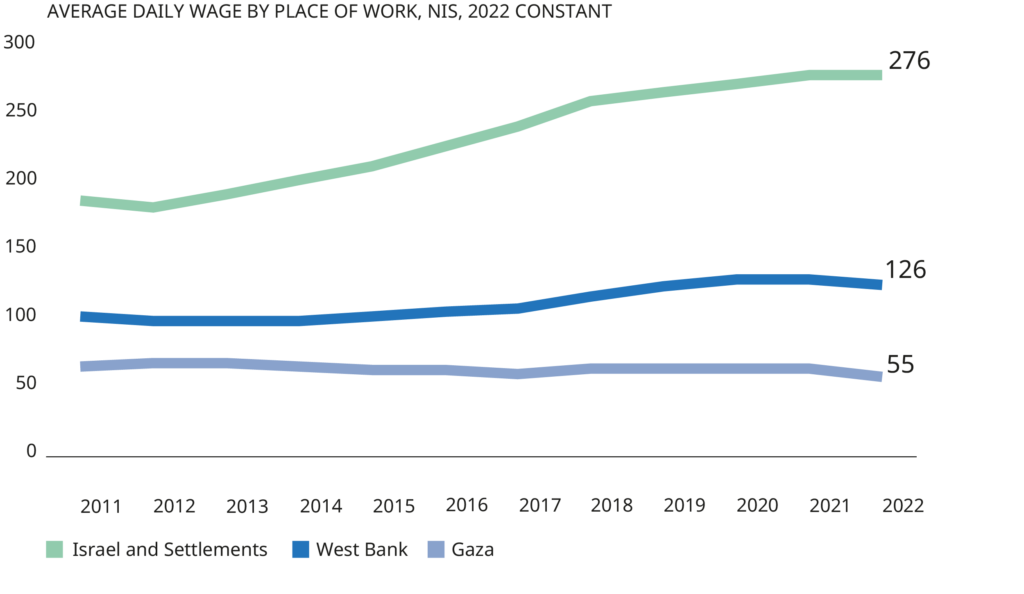

It is also important to note the interconnection through the labor market, with almost 25% of West Bank workers employed in Israel and Israeli settlements in 2022 (Figure 12), attracted by daily wages which were more than double those in the West Bank (Figure 14). However, this imbalance creates distortions in the Palestinian labor market with close to a quarter of all workers from the West Bank working in Israel.

DECOUPLING: IMPORTS AND EXPORTS TO AND FROM israel AS A SHARE OF TOTAL TRADE HAVE BEEN DECLINING

Figure 11 | PCBS (2023c)

BRAIN DRAIN: MORE WORKERS FROM THE WEST BANK ARE SEEKING EMPLOYMENT IN ISRAEL…

Figure 12 | PCBS (2023b)

…AND ACCOUNT FOR CLOSE TO A QUARTER OF TOTAL EMPLOYMENT IN THE WEST BANK

Figure 13 | PCBS (2023b)

EXPANDING WAGE GAP: AVERAGE WAGES ARE LOWER IN THE WEST BANK

AND GAZA COMPARED TO ISRAEL AND THE GAP IS EXPANDING

Figure 14 | PCBS (2023b)

War will have long-lasting consequences for an already fragile SITUATION.

While a thorough, reliable, and comprehensive assessment of the devastation in both Gaza and

the West Bank caused by the war starting in October 2023 is yet to be carried out, early indicators show major, unprecedented impacts on the built environment, production, labor market and beyond.

- The World Bank and UN estimate the cost of damage to critical infrastructure in Gaza at $18.5 billion by the end of February 2024 (equivalent to 97% of Gaza and the West Bank GDP combined).

- About half of all private sector enterprises halted or reduced their activities in Palestine, and there was almost total suspension in production at about 56,000 businesses in Gaza (where more than half of all establishments depend on internal trade).

- Employment in Gaza is at a historic low, with over 150,000 jobs disrupted (exceptions being employees in the health and humanitarian relief sectors). The loss of high-potential youth and a corresponding ‘brain drain’ throughout Palestine exacerbates the negative outlook.

- The almost total suspension of production in Gaza (operating at less than 15% of its capacity) has resulted in losses of around USD 25 million/day (not accounting for direct losses due to destruction of buildings and other assets).

- In the first two months of the war, production in the West Bank alone dropped by 40% compared to the previous year, with an estimated loss of more than USD 1 billion.

- In a conservative scenario, assuming that productivity (measured by GDP per employed person) remained constant between 2022 and 2023, we still project overall GDP to have dropped 50% by year-end 2023.

2050 status quo

Fragmented 7 million population

Continuing conflict migration, exodus across international borders

GDP per capita in Gaza around 50% lower than the mid- 1990s

Hazardous environment, continuing ordnance and rubble removal

Constrained boundaries

Economic imbalances with hinterland

Demographic imbalance, with 65% of the population under the age of 30

Degraded infrastructure

Defunct currency and banking arrangements creating cash and credit shortages

Poor 2G/3G coverage, constraining industrial strategy and logistical arrangements

2050 palestine emerging

Contiguous 13 million population

Attractive territory, focused on transnational trade and exchange

GDP per capita approaching middle-income economy standards

Regenerated next-generation public realm and natural environment

Reduced urban sprawl; proximity of amenities and services

Cost and regulatory advantages relative to neighbors and peers

Youth-oriented human capital for emerging digital sectors

Opportunities for ‘leapfrog’ next-generation technologies

Opportunity to switch to dollar-peg, with (Gulf) underwritten reserves

Total >5G coverage with resilient external physical connectivity and uplink technology

The constrained STATUS QUO Scenario, aggravated by the impacts of the war, need not be the future of Palestine – not least given the implications of instability for the wider region.

Palestine within a Levantine Mega-Region

The Palestinian economy is small. Even with internal barriers removed and borders relatively open, the growth and development prospects for the Palestinian economy will be dependent on its openness and connection to the broader region. Its economic success will inevitably be tied to its ability to engage in greater economic and social cooperation and functioning as part of a transnational region.

In the 21st century, urban regions are becoming more important than ever before; they accommodate most of the world’s population and dominate the world’s economic and cultural life. In this urban age, size matters. Large well-connected regions can draw on a bigger pool of labor and talent, develop more complex and specialized economies, support larger and more effective infrastructure, and leverage their connectivity as global hubs.

Groups of nearby cities work together, sometimes informally, as part of a larger system. In this way they share talent, infrastructure and economic assets. Individual cities can specialize in complementary ways. In doing so, their related populations can perform more strongly together than they could on their own. In some cases, city-regions can cover entire countries, or even span national borders. Such regions do not supersede nations; they optimize economic and social opportunities within the broader territory and make it easier for people to access opportunities.

PALESTINE EMERGING capitalizes on the promise of an ambitious and realistic Growth Scenario. Regardless of any evolving political outcomes, we believe Palestine will develop comparative advantages (including regulatory arbitrage) within its connected territory, which is itself within an evolving Levantine Mega-Region approaching 50 million inhabitants.

PALESTINE EMERGING: THE LONG-TERM VIEW

LEVANTINE MEGA-REGION

(economic structure)

Trade and exchange.

The built-up area of the Levantine Mega-Region encompasses major cities. Despite varying regulatory and political systems, the Levant functions as a coherent trade area, bridging between the economies of Africa and Eurasia. Its reputation for collaboration and connectivity attracts and retains talent and investment, competing with other global megacity regions and large metropolitan areas. Cities within the Mega-Region will continue to specialize.

PRECEDENTS: multinational megacity regions include ‘Greater Bay’ (East Asia), and the ‘Blue Banana’ (Northern Europe).

CONNECTED TERRITORY

(urban structure)

Connectivity.

The formal urban structure of Palestine anchors the political, economic and cultural life of its population. By joining Gaza and the West Bank with strategic connections, it overcomes the constraints of non-contiguous territory. The urban structure leverages infrastructure connectivity to enable mobility of labor, finance and goods.

PRECEDENTS: Luxembourg, Panama, Qatar, and Malta. These areas are distinct from true city-states such as Singapore in that they comprise both their primary city and a number of peripheral cities and towns with autonomous municipal authorities; they also include substantial rural areas.

UNIFIED CONDITION

(legal structure)

Macro-economic stability.

Palestine incorporates a unifying legal framework across Gaza and the West Bank; a range of powers create comparative advantages relative to its peers and within a wider global context.

PRECEDENTS: the regions in Belgium, the cantons in Switzerland, the states of the United States of America, and the emirates in the UAE.