7

growth

PALESTINE EMERGING recognizes the challenges and opportunities for the Palestinian economy are central to all progress.

INDUSTRIAL SECTORS, NEW ECONOMIC PARADIGMS

Gaza has been severely constrained by blockades and restrictions on the movement of people

and goods. This has resulted in a massively undersized economy, chronically high unemployment and low GDP per capita. The current conflict has devastated every economic sector in Gaza, leading to an estimated loss of more than half of output and unemployment above 75%.

Gaza can realize substantial potential once conflict ends and historic constraints are lifted. Given the strong link between poverty and armed conflict, an unprecedented expansion of the economy is essential to improve living standards and reduce unemployment to a sustainable level. The scale of this challenge is increased further by a rapidly-growing population and young age structure.

PALESTINE EMERGING’s growth scenario assumes:

- An end to armed conflict and occupation.

- The easing of restrictions on movement of construction materials.

- A significant internationally-supported reconstruction effort.

- A progressive shift to greater regional openness in the medium-to-long term.

These assumptions are ambitious, but achieving anything less will lead to further economic deterioration, contributing to renewed cycles of violence.

GROWTH SCENARIO

3.5 million population by 2050

610,000 new jobs required (3x increase)

$33 billion annual GDP through unleashing Gaza’s economic potential (10x increase)

540,000 new housing units needed by 2050

10x growth in the construction sector to enable reconstruction

Economic Reconstruction

The physical reconstruction of Gaza will generate a massive economic stimulus in the short-and medium-term. This will require an order-of-magnitude increase in the size of the construction sector compared to the pre-war level. In addition, it will generate secondary activity across a range of other sectors (such as manufacturing, transportation and services). This assumes the availability of international finance for reconstruction, easing of trade restrictions, and capacity-building and skill development to scale the construction sector to the size required.

Recovering Basic Economic Functions

Due to the historical constraints on Gaza’s economy, a range of basic economic functions that serve Gaza’s population were, even before the war, undersized in comparison to a ‘typical’ urban economy. This includes local commerce, basic business services and transportation. As constraints are lifted and the broader economy develops, such basic sectors would be expected to expand, contributing to economic growth.

Emerging Sectors

Beyond immediate reconstruction and recovery, a range of tradable sectors within Gaza can develop a comparative advantage, driving meaningful long-term development. These include agriculture, manufacturing, trade and transportation, tourism, services and the digital economy.

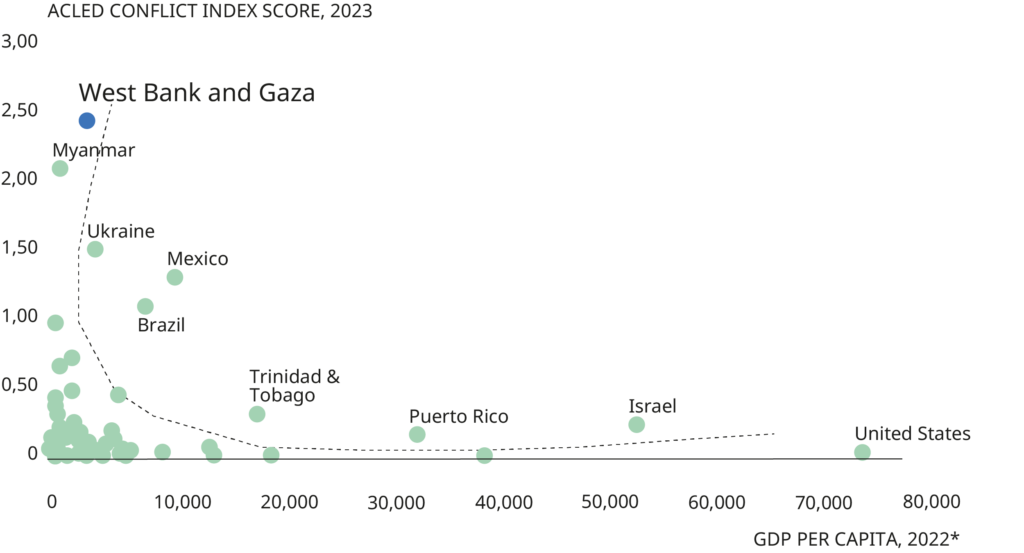

CONFLICT AND GDP PER CAPITA BY COUNTRY

Figure 21 | ACLED

ACLED conflict index assesses every country and territory in the world according to four indicators – deadliness, danger to civilians, geographic diffusion, and armed group fragmentation – based on analysis of political violence event data

*GDP per capita based on latest available data for each country

Without a rapid improvement in economic conditions, the region is likely to experience a continued, vicious cycle of conflict. Research (including UNDP, 2007) provides vast evidence of the close relationship between economic underdevelopment and the likelihood of observing armed conflict: weak economic performance makes conflict more likely; in turn, armed conflict destroys productive assets and interrupts economic activity, resulting in long-lasting negative consequences for economic development. The risks of conflict are heightened in countries with low per capita income, weak and volatile growth, high unemployment (particularly among youth) and horizontal inequalities, conditions which are all prevalent in Gaza.

Figure 21 shows the statistical correlation between GDP per capita and conflict, based on the Conflict Index of ACLED for a large sample of countries. As shown in the Figure, Palestine has one of the lowest GDP per capita figures and one of the highest conflict intensity scores, higher than that of Ukraine.

Modeling Results

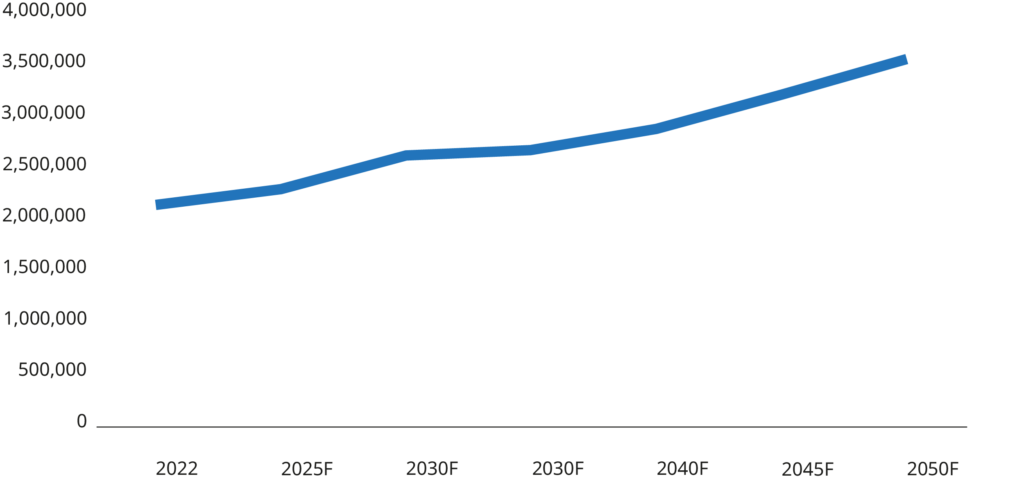

Gaza’s population is projected to increase from around 2.2 million in 2022 to 3.5 million by 2050. This accounts for demographic factors (e.g. age structure and fertility rates). It also assumes a level of economically-driven emigration, including to the West Bank, as restrictions on movement are eased.

GAZA POPULATION PROJECTION, 2050

Figure 22 | TEAM ANALYSIS

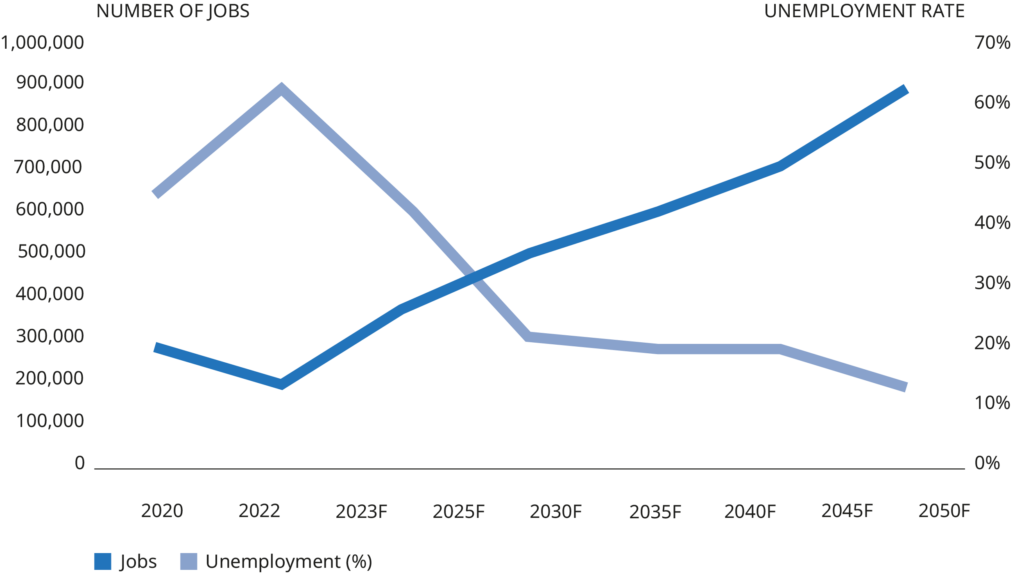

Under the assumed conditions, Gaza’s employment base could grow to nearly 900,000 by 2050, eventually bringing unemployment down to sustainable levels. This requires creating 610,000 additional jobs by 2050, more than tripling the size of the pre-war employment base. This also assumes a share of the Gazan labor force working outside Gaza (West Bank or Israel) in the longer term.

GAZA JOBS AND UNEMPLOYMENT RATE PROJECTION, 2050

Figure 23 | TEAM ANALYSIS

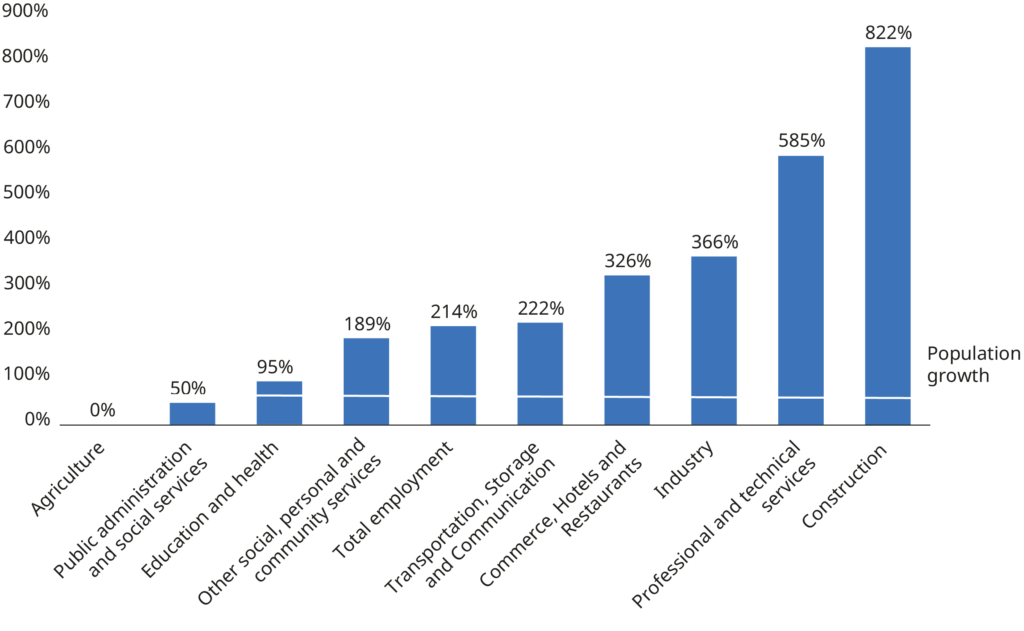

Sectoral Change

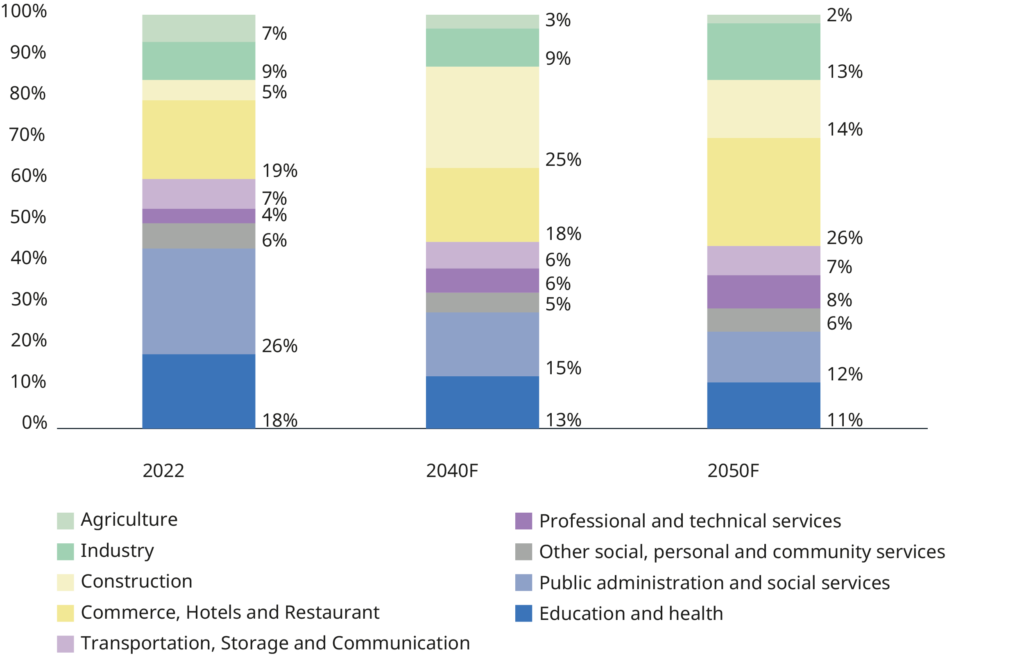

Figures 24 and 25 demonstrate the sectors underpinning employment growth.

- Construction could increase massively in the medium-term to meet reconstruction needs, and remains a large sector going forward to support population growth.

- Commerce, Hotels and Restaurants are currently undersized relative to Gaza’s population. This could grow significantly in the long term to reach a more typical size relative to population, eventually contributing the largest absolute number of jobs.

- Tradable sectors – including Industry and Professional and Technical Services – will grow consistently in the medium-to-long term as Gaza develops international competitive advantage.

- Social, Personal and Community Services, Public Administration and Education and Health grow as a function of population.

- Agriculture remains constant as it is limited by available land, though productivity within the sector could increase.

EMPLOYMENT BY SECTOR PROJECTION

Figure 24 | TEAM ANALYSIS

EMPLOYMENT GROWTH PROJECTION

Figure 25 | TEAM ANALYSIS

EMPLOYMENT BY SECTOR PROJECTION

Figure 26 | TEAM ANALYSIS

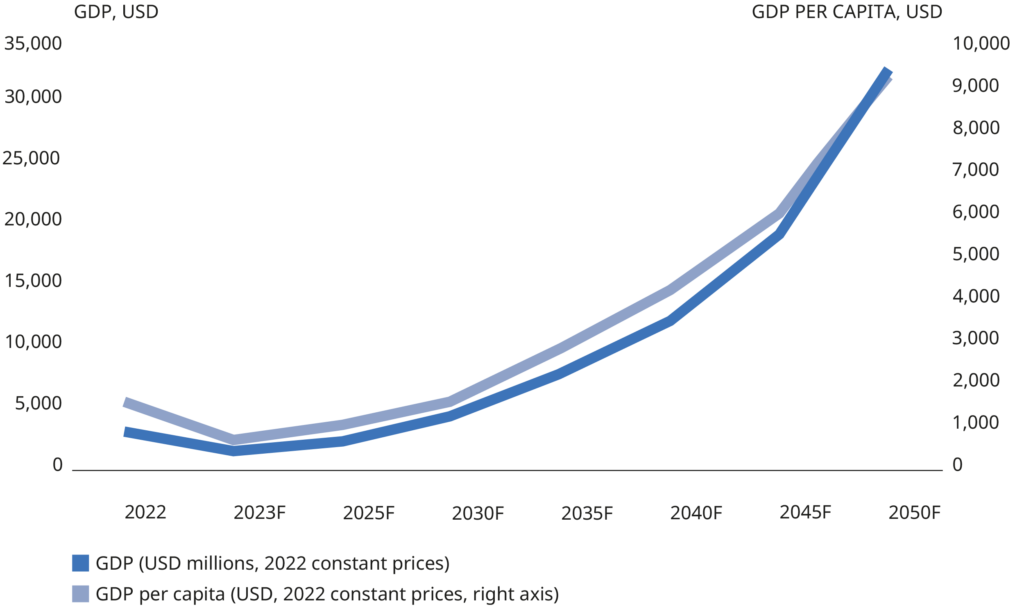

GDP

If the scenario above can be achieved, while also growing productivity within sectors, Gaza’s per capita GDP could reach over USD 9,000 by 2050, achieving the status of a middle-income economy. Following immediate recovery from the war, this would require sustaining a total GDP growth rate of 10% per year between 2030 and 2050.

GAZA GDP PROJECTION

Figure 27 | TEAM ANALYSIS

Strategic Economic Sectors

The following strategic sectors have particular potential to drive Gaza’s economic transformation and long-term competitive advantage.

Construction

Rebuilding from the current conflict and addressing pre-existing deficits of housing and infrastructure will require upscaling of the construction sector beyond any past historical level. Gaza will need to construct more than 540,000 dwellings by 2050, or more than 20,000 per year on average (comparable to annual housing completions in London); this effort will require an extraordinary capacity-building and upskilling program. The construction sector will expand in the short-to-medium term and remain large in the long term to support ongoing population growth.

Manufacturing

Developing manufacturing will require re-investing in facilities and capital which have been severely damaged during the war. Reconstruction and rehabilitation will create significant demand for construction materials, which will stimulate the local manufacturing sector. There will also be natural growth across many light manufacturing activities, including food and drink processing and basic consumer goods serving local needs.

In addition, Gaza can recover and develop historic, craft intensive industries such as furniture and garments, though these are likely to remain relatively small and niche. In the longer term, Gaza can seek to develop export-oriented manufacturing, leveraging its latent strengths including labor cost advantage and a high skills base.

Trade and Transportation

In the earlier phases, lifting of restrictions will induce significant growth in trade, logistics and transportation. It will re-establish basic functions necessary to bring goods to the population, connect manufacturers to raw materials and export markets, and service passenger transport. The Gaza Port and the Gaza West Bank Link will be the largest stimuli for trade.

In the long-term, amid greater regional openness and interconnection, Gaza could take on a broader role as a transportation gateway serving the region. Such a role has great historical resonance for Gaza, which has been a trading hub on the Levantine corridor for much of the last 5,000 years.

Digital Services

The tech sector has high potential to drive economic development in Palestine. It builds on Palestine’s key comparative advantage (its young, entrepreneurial and skilled population),

to generate high value-added enterprises, and support high female participation rates. Palestine can leverage its advantageous time zone, English and Arabic proficiency and competitive cost base to export services across the Middle East, wider region and the world. In the short term, the growth will focus on recovery of the outsourcing sector, secured by loss guarantee instruments

to attract investment. Further investment in education will be required to unlock the potential of these sectors, which will accelerate in the longer term.

Tourism

Palestine has rich tourism assets stemming from its history, culture and Gaza’s mediterranean coastline, which could support growth of the tourism sector following re-construction and the easing of movement restrictions. These assets will attract regional and international interest;

the sector has potential to support 160,000 jobs and generate USD 2bn pa by 2030. It will be important to address safety perceptions and movement restrictions to support a world-class medium-term tourism offer, drive small businesses, and create jobs. Initially the main drivers are likely to be domestic and Palestinian diaspora visitors (for example, there is a strong desire for West Bank residents to visit Gaza’s coast). International tourism could increase in the longer term, attracting wealthier independent tourists and young adventurers in the rapidly-growing “ESG” global tourism segment who seek experiences related to social justice, authentic culture, economic development and sustainability.

Agriculture

Gaza is notable for having an agricultural sector with high yields, although at the expense of depleting the aquifer that supplies water for domestic needs. While the absolute size of the sector is limited by available land and water, Gaza can continue to increase productivity, and rationalize crop selection. Doing so will help Gaza develop associated value chains for domestic consumption and high-value export. The agricultural sector is important for its contribution to food security. Managing water consumption to avoid unsustainable extraction from the aquifer will be critical.

TRAVEL GATEWAYS

Several countries, like Morocco, have created digital travel booking gateways to facilitate provision by local tourism providers, enhancing travel experiences and empowering local businesses to share their unique offerings on a global stage. Visit Oman offers a sound organizational model which would help Palestine push into a tightly-targeted and growing market segment.

CHRISTMAS IN BETHLEHEM

Bethlehem’s Hebrew/Aramaic name means ‘house of bread’, acknowledging the area’s original reputation for growing wheat. Only about 20% of Palestinians are Christian, but many Muslim Palestinians are also proud that Jesus was born in a Palestinian Territory. Christmas Eve is celebrated in the Church of the Nativity, led by the Roman Catholic Bishop of Jerusalem.

Christmas is more widely celebrated in the State of Palestine / Palestinian Territories than it is in Israel.

GAMECHANGER

TRADE, CURRENCY AND STANDARDS PIVOT

As power and water are for existence, so money and trade are for the economy. Even with a smoothly functioning internal market, Palestine is a small inward-looking economy with a high trade deficit; more trade is a central requirement for economic progress.

Create leverage over key macroeconomic factors to re-orient the Palestinian economy towards stronger long-term economic growth. Reform existing customs union arrangements; create monetary stability and adopt a set of common, export-oriented, standards across Gaza and the West Bank.

Focus on international trade with a “Made in Palestine” brand, creating a strong ‘trade-not-aid’ push. Attract investment through bilateral goodwill trade agreements with the EU, US and the Arab world of some 500m customers. To increase value from trade, create a new framework that removes restrictions on the free movement of goods. Prioritize financial support to export-oriented sectors and activities.

To support international trade, reduce currency risk and pivot away from the Shekel. Regular and severe cash challenges caused by the current monetary arrangements create systemic risks and impede the availability of local credit; an alternative monetary framework may offer significant benefits and an additional lever of economic policymaking, provided the arrangements replacing it are at least as strong. Global experts are prepared to inform and support this discussion.

In 1983, Hong Kong introduced the Linked Exchange Rate System (LERS), tying the Hong Kong Dollar (HKD) to the US Dollar (USD), which has since fostered a stable monetary climate conducive to economic growth. Although the currency board setup may limit the Monetary Authority’s control over monetary policy, the 2005 establishment of a convertibility zone between 7.75 and 7.85 (USD to HKD) signified the Hong Kong Monetary Authority’s commitment to intervene by buying or selling USD to maintain the exchange rate within this specified range. Regarding interest rates, which follow the USD and are influenced by the supply and demand for the Hong Kong dollar, the substantial deposit base within Hong Kong’s banking sector has enabled major banks to manage their funding costs effectively. The combination of a currency board system and prudent exchange rate and currency reserve management can strengthen a government’s fiscal stability.

GAMECHANGER

PALESTINIAN FUND FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT (PFRD)

A dedicated and independent Palestinian-led financial reconstruction and development vehicle will credibly attract and manage major reconstruction funds. Endorsed by international institutions, sovereigns and finance partners, PFRD will fund and support core infrastructure projects. It will raise capital from all global reconstruction partners, leveraging private finance. It will oversee the correct establishment, financing, and delivery of enabling infrastructure projects. The PFRD will also enhance local financial and accountability expertise.

INTERNATIONAL COORDINATION

PFRD will significantly enhance the quantum of investment and funding flowing in from international donors, agencies and leveraged funding, initially for Gaza reconstruction but also for West Bank development. With rigorous international oversight, it will complement and support the delivery of Palestinian reconstruction with financing and co-investment through local vehicles.

ADVISORY AND TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE

PFRD will provide advisory and technical assistance, pooling and drawing from the institutional capabilities of international donors and funders, ensuring alignment, critical mass and leverage rather than duplication and competition.

LOCAL CAPACITY BUILDING

By design, PFRD will select and train local talent to fulfil the roles it will be mandated to deliver, increasing local staff over time, including through Palestinian secondment to global institutions, enhancing talent for the broader banking ecosystem.

BAD ASSETS FUND

Given the scale of loses in Gaza, banking system stability requires a bad-asset fund, with specialist asset management capable of addressing balance sheet liabilities.

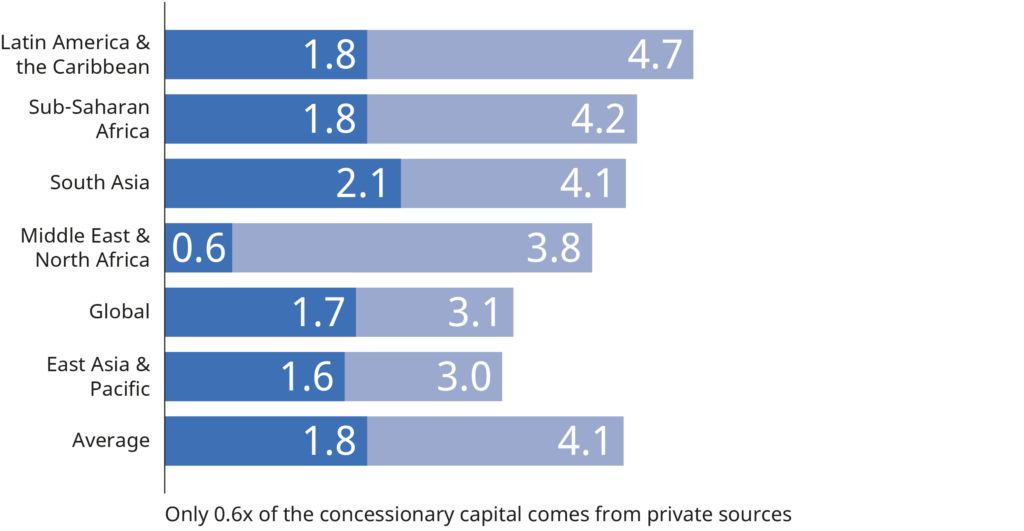

ME&NA HAS ONE OF THE LOWEST PRIVATE SECTOR MOBILIZATION RATIOS IN THE WORLD, SUGGESTING HIGHER PERCEIVED RISK

Figure 28 | APAMPA (2023)

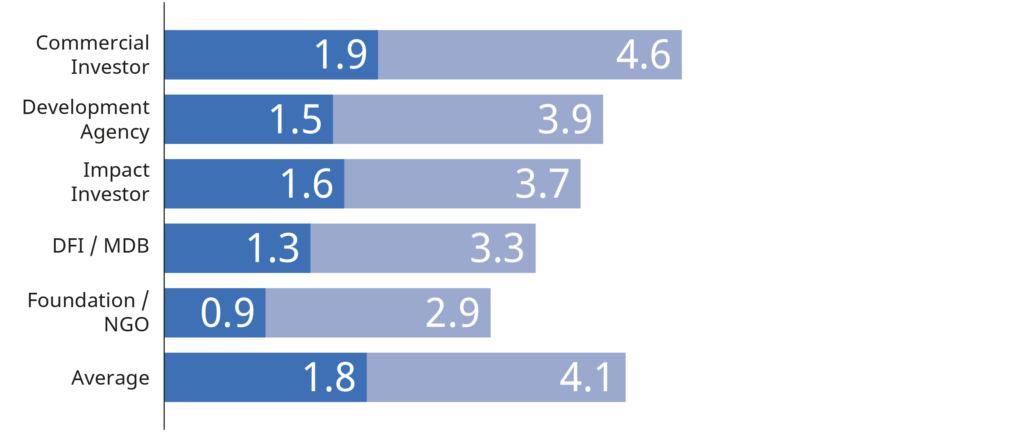

COMMERCIAL INVESTORS ORIGINATE DEALS WITH HIGH LEVERAGE RATIOS, IMPACT INVESTORS AND DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES COME A CLOSE SECOND AND THIRD

Figure 29 | APAMPA (2023)

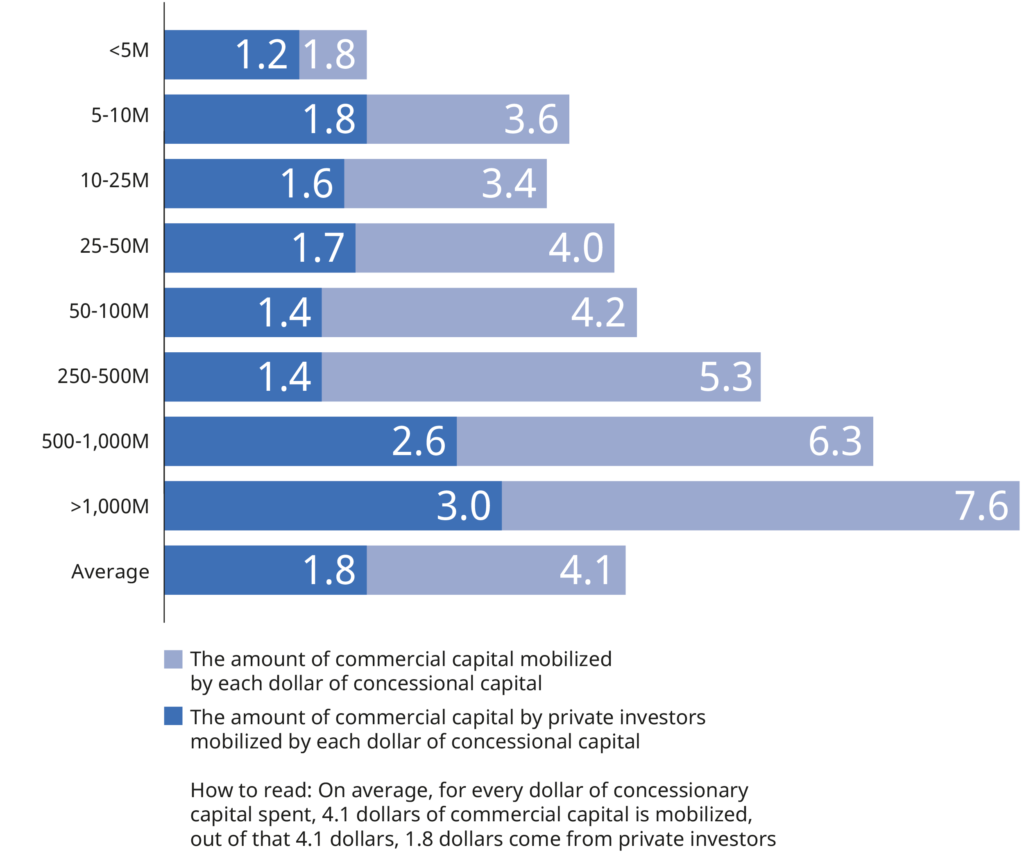

LEVERAGE RATIO INCREASES WITH DEAL SIZE, HIGHLIGHTING THE BENEFITS OF DEAL AGGREGATION

Figure 30 | APAMPA (2023)